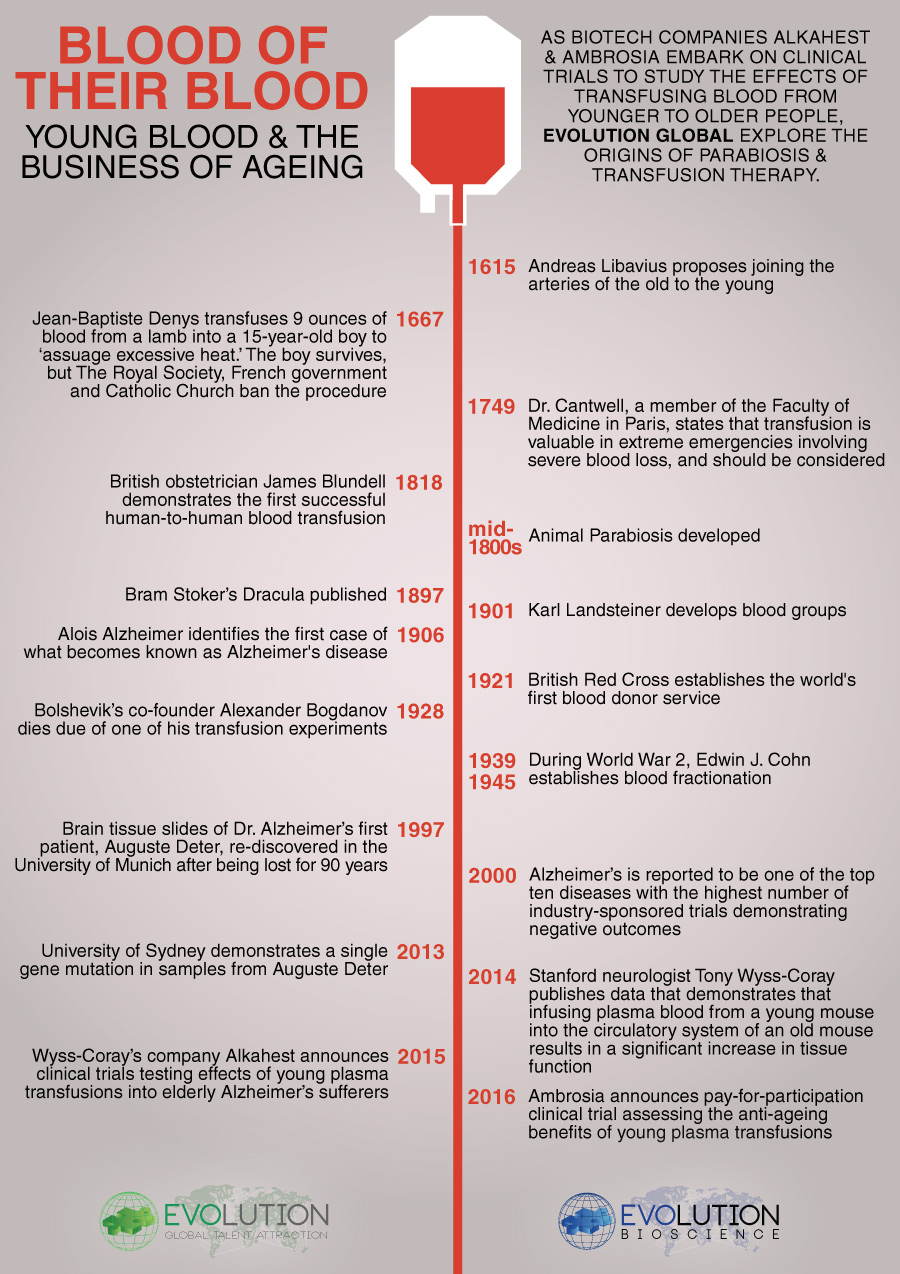

The concept of transfusing blood from younger to older individuals has returned to the spotlight in recent years following the commencement of clinical trials by US companies Alkahest & Ambrosia. However, the idea of transfusing blood from young to old is not a novel concept, and similar to our recent article on the origins of cancer immunotherapy, the concept has in fact been around for centuries.

A Historical Perspective

Its origins stretch as far back as the 17th Century, when Andreas Libavius proposed connecting the arteries of a young man to an older one citing ‘blood of the young man will pour into the old one as if it were from a fountain of youth, and all of his weakness will be dispelled.’ There are no records if the approach was tried for ageing, and given the lack of knowledge about blood types and blood-borne infections, it would more than likely have been a very risky prospect.

In the early part of the 20th century Alexander Bogdanov, one of the co-founders of the Russian Bolsheviks, started his blood transfusion experiments apparently hoping to achieve eternal youth or at least partial rejuvenation. After undergoing 11 blood transfusions, he remarked with satisfaction on the improvement of his eyesight, suspension of balding, and other positive symptoms. The fellow revolutionary Leonid Krasin wrote to his wife that “Bogdanov seems to have become 7, no, 10 years younger after the operation”. In 1925/1926, Bogdanov founded the Institute for Haematology and Blood Transfusions, which was later named after him. However, a later transfusion cost him his life, when he took the blood of a student suffering from malaria and tuberculosis.

Running in parallel was an increased interest in parabiosis, a process in which the circulation of two living organisms are joined together surgically to create a shared circulatory system. Pioneered by the great French polymath Paul Bert, also known as ‘the Father of Aviation Medicine,‘ the technique fell out of favour until the 1950s when it was resurrected for studies involving metabolism. Studies have been ongoing for different research purposes ever since, albeit at a small scale.

Modern Developments

In 2014 Stanford neurologist Tony Wyss-Coray published data that demonstrated that infusing plasma blood from a young mouse into the circulatory system of an old mouse resulted in a significant increase in tissue function. Brain tissue was among the areas showing improvement, offering the tantalising prospect of improvements in conditions such as Alzheimer’s. As this could be achieved without permanently connecting circulatory systems, the potential for a translatable therapeutic route is possible.

Wyss-Coray’s company Alkahest is currently carrying out a randomised, double-blind study involves 18 people aged 50-90 with moderate to severe Alzheimer’s. For one month, each patient will receive a weekly plasma injection from donors aged 30 and under, in addition to a four-week course of saline as a placebo, with six weeks between the treatments. They will then be subjected to multiple rounds of testing for mental acuity, and their caregivers will watch them closely for behavioural changes. The results are expected at the end of this year.

The intention of the Ambrosia LLC clinical trial assessing the anti-ageing benefits of plasma is to assess the effects of transfusions on an array of biomarkers. The trial involves 600 people over the age of 35, who will receive 1.5L of plasma derived from healthy donors aged 16-25 over a two day period. Before the infusions and 1 month after, their blood will be tested for more than 100 biomarkers that may vary with age, from haemoglobin level to inflammation markers. Of note is the fact that Ambrosia’s trial uses a pay-for-participation model, with candidates expected to pay an $8000 fee to cover the trial costs.

The Ambrosia trial can be viewed as being targeted towards the narcissistic end of the worried well spectrum and has quite rightly raised many ethical concerns, with many commentators stating that this is the last roll of the dice for the ageing baby boomer generation seeking to feast on the blood of a new generation who have significantly less economic prospects than they did. However, it is important to recognise that the trial is very thorough in terms of its selection of key biomarkers, which may well highlight key individual biomarker positive effects that could potentially point the concept towards more pressing healthcare needs in the future.

Given that Alzheimer’s is the greatest challenge due its distressing nature, costs and lack of success of new treatments, one can only hope that Alkahest’s clinical trials generate positive results. Regardless of the results of these clinical trials, the idea of transfusing young blood into older people will continue to be explored by researchers for a variety of reasons, both therapeutic and narcissistic.

You can download a PDF copy of our Young Blood Transfusion Timeline via the button below: