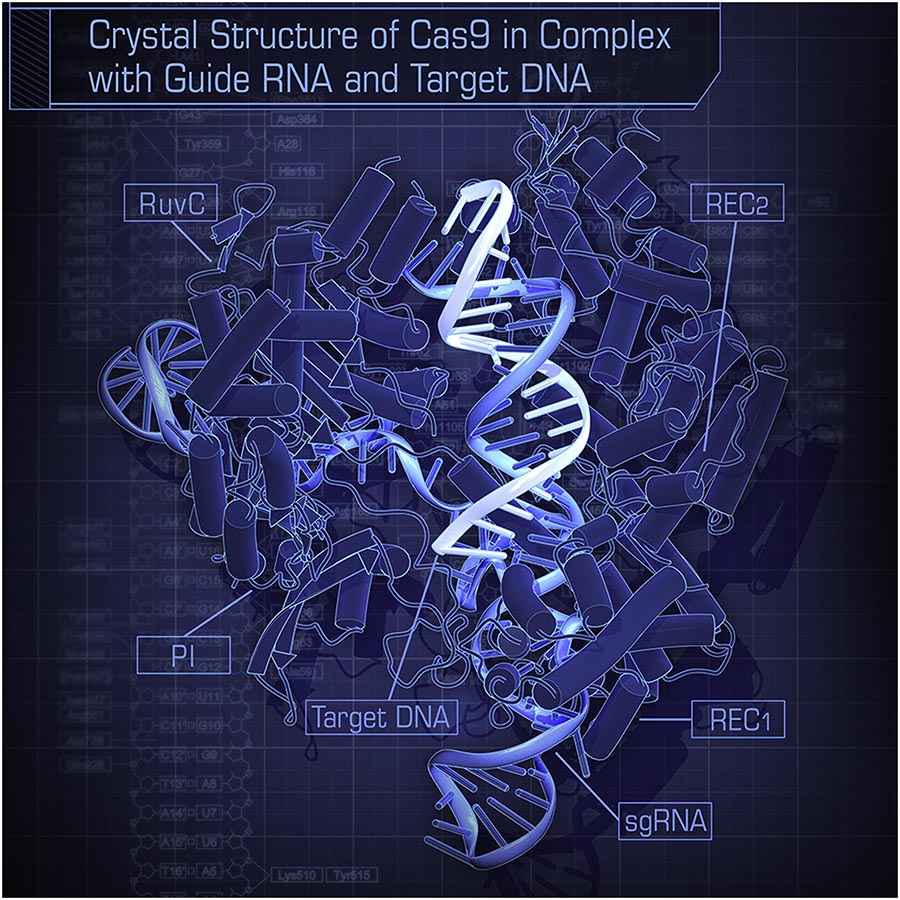

The UK’s Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA) has given the go-ahead for a select group of Francis Crick Institute researchers to edit the genomes of human embryos. The group, led by developmental biologist Dr. Kathy Niakan, will utilise CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing technology to examine embryo behaviour in the first week after fertilisation in order to better understand issues such as miscarriages and infertility.

Specifically Dr. Niakan and her team will be running test tube experiments that involve blocking a specific gene (OCT4) that is thought to play a role in fetal formation. The researchers are permitted to study the embryos for research purposes only, and the development of the embryos will be terminated after 7 days. It is important to note that this decision preserves the distinction between research purposes and clinical applications.

The use of CRISPR-Cas9 is a very heated and divisive area of research. Given the promise that this elegant, simple and inexpensive gene editing technology can offer, CRISPR-Cas9 has sparked an ethical debate that has fiercely divided the scientific community. As a technique, the method has taken the life science world by storm.

“It’s likely that the pioneering human cell culture work in 2012 by US-based Doudna and Charpentier can be considered the true inflection point of the technique,” notes Dr. Frank Rinaldi, Director of Market Intelligence & Innovation at Evolution Bioscience. “Since 2012, growth in groups adopting CRISPR and concomitant publications are accumulating at a rate of 35%, and there are now some 12,000 research groups with an active interest in using the methodology worldwide. Areas of focus range from cancer, infectious disease research through to Agbio applications.”

Dr. Rinaldi believes that “ultimately the elevated attention is due to the fact research groups worldwide are now getting to a point of significantly reducing the so called ‘off-target’ editing errors by re-engineering the Cas9 enzyme that is used. Recent CRISPR publications by researchers at the Broad Institute of MIT & Harvard and the McGovern Institute for Brain Research highlights the progress being made.”

The correction of monogenic genetic disorders using CRISPR-Cas9 has been an area of much discussion in recent years. This debate was reignited in April of 2015, when Chinese scientists reported the successful germline modification of human embryos using CRISPR-Cas9. The Alliance for Regenerative Medicine in Washington DC is seeking a global moratorium on modifying human embryos, sperm and eggs, regardless of clinical or research applications. The US National Institutes of Health has already stated that it will not fund any genome editing research on human embryos.

“The recent announcement of the UK-approved application is somewhat at odds with the US stance, and will create a research divide in Western World Research,” predicts Dr. Rinaldi. “The situation is not unlike the original development of stem cells from discarded embryos, which resulted in a clear divide. This was only healed via the discovery of induced pluripotent stem cells which are derived from adult cells and reprogrammed to a stem cell state.”

“Ultimately the debate is about the ethics of using discarded embryos in this manner, not the promise that such research may hold,” concludes Dr. Rinaldi. “All that can be stated definitively is the fact that the overarching ethical issues remained unresolved the last time around, even after vigorous debate. Given the conflicting global opinions on germline modification of human embryos, it is highly likely that the ethical issues will remain a hot topic of debate in years to come.”

Evolution has been working to optimise the human genome for 3.5 billion years. Will ‘human gene’ engineers help or hinder? An interesting discussion awaits…

Follow Evolution Global Talent Attraction on LinkedIn, Xing, Twitter and Facebook to keep up-to-date with news and trends from the biotechnology, biosciences, medical device, IT and Intellectual Property industries.